Tranalysis

On the afternoon of May 30, 2024, the Institute of Humanities and Social Sciences of Peking University and the Sanlian Bookstore of Life, Reading and New Knowledge jointly held a reading session entitled "Contributions and Limitations of In-depth Comparative Historical Analysis-" The Path to a Modern Fiscal State "in Conference Room 208 of the Second Hospital of Peking University. The meeting was introduced by Wen Kai, author of the book "The Path to a Modern Fiscal State" and associate professor of the Department of Social Sciences at the Hong Kong University of Science and Technology. Zhang Changdong, professor of the School of Government at Peking University, Tian Geng, associate professor of the Department of Sociology at Peking University, and Du Xuanying, associate professor of the School of History at Renmin University of China, Han Ce, associate professor of the Department of History at Peking University, and Cui Jinzhu, lecturer at the School of History at Capital Normal University, commented. Due to space limitations, the text of this book meeting is presented in three parts. This article is a review by five scholars on "The Path to a Modern Fiscal State".

Du Xuanying (Associate Professor, School of History, Renmin University of China):

This book had a great impact on me, because when I first came to study in the UK, the biggest academic impact I received was that training in Chinese political history was first based on the system. However, Britain's early modern political history training has now divorced from the institutional level. From the 19th century to the mid-20th century, British political history research basically centered on institutional history, but by the late 20th century, it began to break through the explicit "system" and move towards the implicit "relational perspective." In recent years, many researchers seem to be worried that institutional research may become "lost history", prompting historians to gradually return to institutional research, but adopt a different perspective. This book by my teacher and other historical research in recent years show the same trend in the study of institutional history. Let me talk about my understanding of this book, especially the British history section.

First of all, the content of this book in British history mainly explains the fiscal development of the English regime in early modern times, including the control of information, the expansion of finance and the institutional changes it led to. The changes in the relevant fiscal and taxation systems include changes in bureaucracy, tax system, national debt, currency, distribution and other aspects. This book hopes to reexplain Britain's rise through the series of changes triggered by finance (revolutions in political and economic systems). Teacher He placed his research perspective in a macro historical context and inspired us to rethink why the entire Europe was generally faced with the price revolution and absolute monarchy of the 16th century, but only Britain from the 17th to 18th centuries entered the stage of a modern fiscal state?

The book mentions that absolute monarchy and the price revolution of the 16th century led to Britain's financial difficulties, which in turn caused tensions between the monarch and parliament. In fact, the relationship between parliament and monarch differed from one time to another. For example, during the Stuart period, the monarch and parliament were at odds, but during the Tudor period, the relationship between the two was relatively relaxed. Because the Tudor period had a culture of "men of business", the royal family and dignitaries arranged people to enter the House of Commons to manage and assist in passing bills. In the Stuart Dynasty, it was precisely because no "agent" was arranged that strained their relations. In addition, in the 17th and 18th centuries, the Stuart Dynasty overthrew the Tudor tradition of isolated diplomacy and participated in European wars, encountering domestic and foreign troubles. On the one hand, there is tremendous pressure from external war; on the other hand, internal revolution and financial crisis are also imminent. The political crisis formed internally and externally triggered subsequent changes. The reforms discussed with my teacher inspired me to rethink, such as the highly bureaucratic institutions pointed out in the book, but whether Britain had reached highly bureaucratic at that time in early modern times is a question I want to ask my teacher. Why did the English regime in early modern times suddenly transform from a ruling team with aristocrats at its core in the Middle Ages into a highly bureaucratic administrative group?

Teacher He's book constructs a very large historical picture, describing the construction process and overall structure of a "modern state" or "modern government". This book focuses on the important British historical debate in the mid-20th century, namely Jeffrey Elton (G. R. Elton's "Tudor Government Change Theory" opens up this history from the perspective of the fiscal and taxation system. Elton believes that the Henry VIII regime was successively promoted by two ministers to change the government system, making the "modern","bureaucratic" and "national" government system appear in advance in the early 16th century. This theory has been criticized a lot. The book with my teacher actually re-promoted discussions in this field and allowed me to see the return of "new institutional history" or "new political history."

I would like to ask my teacher three questions. First, this book presents the highly institutionalized regime in early modern England. For example, it mentions the institutionalized operation of central government documents in the early 17th century and the role of the king as the supreme ruler of the country rather than an individual. But have we overestimated the degree of institutionalization and actual implementation of the regime or government in early modern England, especially in the 16th and 17th centuries? After Elton proposed the "Tudor government change theory", David Starkey countered that what dominated the entire regime at that time was not the institutional level, but the king's "natural body" and its extended human network. In other words, the inner court, where the king's "natural body" is located, rather than the government, is the real core of power.

Therefore, when the king rules the country and government, he does not rely on the system, but on his personal relationships to operate. This is what Starkey's theory of "the politics of intimacy" emphasizes. "Intimate politics" was also significantly reflected in the Queen Elizabeth period. On the one hand, officials criticized the Queen's internal court system and interpersonal intervention policy formed through a "natural body", but on the other hand, officials also copied a private visitor culture in their private homes to interfere in political operations. In other words, the inner court and door system formed a stable "dual-track system" during the Tudor period, that is, a political culture in which "relations" and "institutions" were parallel. This is especially evident in the area of documents. Although a system of government documents was established during the Tudor period, if you examine the national archives, you will find that the real handler and administrative center of central government documents at that time were not in the government. In the private residence of the Principal Secretary of State who held administrative documents, it can be found from the handwriting that all documents were written by doormen, and few doormen served as government officials. All in all, the first question is whether we overestimate the role of "institutions" in British politics in the 16th and 17th centuries.

The second question concerns the fiscal aspect. The Tudor regime has many hidden finances that circumvent supervision. For example, the Queen's officials raise a large number of spies, and the remuneration method is not paid by the national treasury, but by the Queen's personal treasury. This purpose is to circumvent government supervision and flexibly strengthen the Queen's ability to control finances. Among them, the Queen will also grant special favors to outstanding spies. For example, the family of spy Nicholas Berden received privileges as a royal poultry supplier. These are all hidden potential fiscal expenditures. On the other hand, the royal family also realized profits through feudal custody or investment. We should pay attention to hidden fiscal expenditures and incomes, and through the above-mentioned documents, power operations and finances, we can see that Tudor politics presents a "wild state", that is, although there is a formal system, everyone is outside the system.

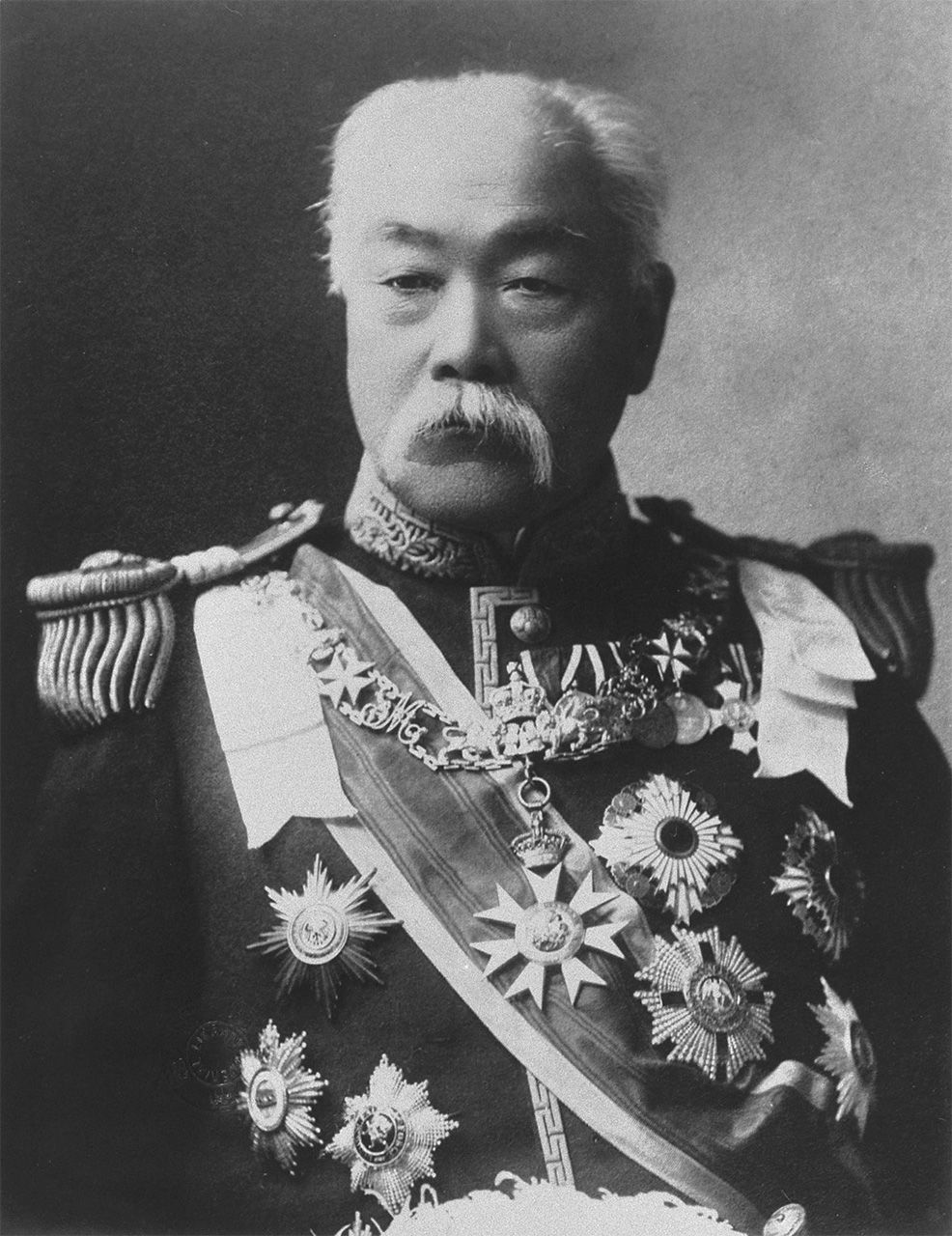

Francis Walsingham, First Secretary of State for Elizabeth I

This involves another issue, namely the bureaucracy. Teacher He pointed out that highly professional and institutionalized bureaucrats appeared in the 17th century. Why did the British regime, which was wandering inside and outside the system in the early modern era, suddenly form such a bureaucratic group? In the Middle Ages, aristocrats did not receive professional administrative training. Why did they eventually form such professional bureaucrats? Mainly during the Tudor period, when document administration basically relied on the doorman system. Part of the reason why these people become doormen is that they have no way to achieve promotion through normal channels, and instead rely on powerful people and become private doormen. The origins of this group of people were different from the gentry and aristocrats. Most of them came from merchant families. Based on their family background, investment knowledge or professional needs, they became professional visitors after receiving law (rather than economics) training at Oxford and Cambridge Universities, as well as the Bar School. Those who perform well are recommended to the central government to serve as dignitaries 'ears and ears in the government, or placed in the House of Commons to form the "agents" described earlier. In short, the reason why this group of people become highly professional bureaucrats is not because of the system. They benefit from their own private background such as relatives 'geographical relationships, the network of chambers of commerce or investment in chartered companies, and are able to collect and control accurate tax information. Therefore, a large amount of tax revenue can be achieved and the fiscal system can be improved.

The last question is that in his book, he mentioned three types of fiscal and taxation changes-taxes, debt, currency (also paper money), and their related credit crisis when Britain entered the fiscal state stage in modern times. The credit crisis is not only reflected in business and property taxes, but also reflects the change in identity and trust of the guarantor behind it. This involves the tendency to strip off the "monarch's body" and its long-term impact on the subsequent concept of trust. During the Middle Ages,"monarch" and "state" were tied together. However, during the period discussed in the book, that is, during the construction of modern states,"king" and "state" began to be cut, so the change of state sovereignty would affect the credibility of the original guarantee object, namely the monarch. Related to this, the public's perception of the guarantee ability of the "monarch" or "state" as a sovereign has also affected the transfer of the attributes of taxes, debts and currencies from the private attributes of the monarch to the public nature of the country, which is worth discussing.

Cui Jinzhu (Lecturer, School of History, Capital Normal University):

There are two chapters in Teacher He's book about Japan during the Meiji era, from 1868 to the Sino-Japanese War in 1895. When I was writing my doctoral thesis in 2015, I read the English version of the book and gained a lot. Of course, I also had some questions. I mainly talk about my understanding from two aspects.

First, although this book compares the United Kingdom and Japan and discusses the same system, I think there are obvious differences between the two. Because the United Kingdom can be regarded as a "primary" fiscal country, while Japan is just an imitation or "secondary/latecomer" country, the two cannot be regarded as the same. The second question is actually related to the first question. Teachers and teachers tend to deny the role of individual initiative, and adopt a relatively negative or negative attitude in a series of statements, believing that when faced with crises and specific social structures, individuals (including smart leaders) cannot grasp all the situations and cannot make absolutely rational choices. At this time, the previous issue is involved, that is, Japan is likely to be different from the United Kingdom in its original state.

In terms of materials, in addition to second-hand papers and works, the Japanese part of this book mainly uses Okuma Tokumoto (Shigeobu Okuma was in charge of Japan's finance and finance before 1881) and personal information about Masayoshi Matsuda (who was in charge of finance and finance from 1881 to 1895), and also borrows information from Eiichi Shibuzawa and Tomohiro Goyo. In short, what they use is their personal data. Of course, what they record is government matters, but the documents are all their personal things. But on the other hand, Teacher He denied that these people were not rational enough, lacked knowledge, and were not enough to grasp the actual situation, so they would definitely make mistakes in a situation where the entire social and economic structure was large. It is normal for mistakes to occur, but I think we need to discuss how to make such a judgment based on proportion.

Masayoshi Matsudata

I mainly read Matsukata Masayoshi's documents and focused on his expansion process. Specifically, it refers to how Masayoshi Matsukata carried out political reforms since 1881 in the face of the dual background of domestic political reshuffle and foreign international crises. By examining Masayoshi Matsukata's correspondence with others in the 1870s, 80s, and 90s and the various policy documents he himself edited, I think we cannot underestimate these young revolutionaries too much. Because they were only about 30 years old when they started the revolution, in their prime of life, their considerations and judgments on many things actually exceeded our imagination. Therefore, the views emphasized by Teacher He may be applicable to the United Kingdom, but they need to be discussed again for Japan and the late Qing Dynasty as a late-developing country. Of course,"latecomer advantage" is a term in modern society, but this does not affect our understanding of Japan at that time in this sense. Moreover, judging from the historical data of these leaders who made key political decisions, Japan does have the advantage of being latecomer.

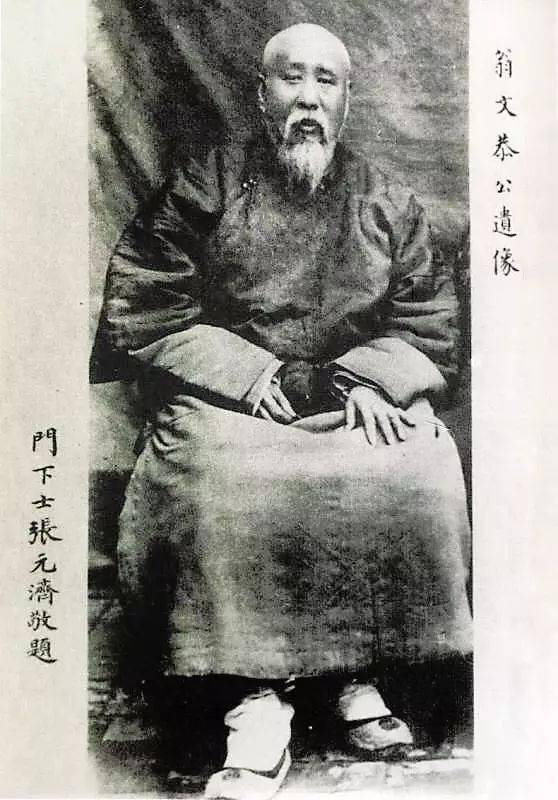

Next, I make a comparison between China and Japan during the same period. Weng Tonghe was a traditional scholar-official who had been in charge of the Ministry of Revenue for a long time. Weng Tonghe was the main person in charge of the compensation and borrowing in the 1894 - 1894. He should be regarded as one of the final decision-makers. I read Weng Tonghe's documents and found his correspondence with Prince Gong Xin very interesting. Weng Tonghe often wrote in his diary that Xu Jingcheng, the Minister to Russia, sent a telegram full of modern financial terms. Weng Tonghe always asked what the telegram meant. The same message was also sent to Yan Xin, who immediately wrote to Weng Tonghe saying that it was troublesome not to understand these financial concepts. For example, the telegram said that if you borrow money in the name of the Qing government, the interest rate will be 6% or 7%. If you add the guarantee from the Russians, the interest rate will be reduced to 3.5% to 4%, which can save a lot of money at once. As a result, Weng Tonghe was very happy when he saw it. But Yushin immediately reminded him that he could not do this. Doing so would mean that we might become a protectorate of Russia. Then Weng Tonghe immediately reflected and said that he really didn't understand anything.

Looking at Matsukata Justice on the other hand, it shows a completely opposite state. He often confidently said that when he was in his 30s, he went to France and sat down with the former French finance minister. He learned a lot of experience from it, such as whether foreign national bonds can be borrowed and the reasons why they cannot be borrowed, and what specific rules are in international law for borrowing foreign money.

Therefore, I feel that we cannot underestimate the learning ability of late-developing countries like Japan, because they already have targets to imitate and are very clear about examples of successes and failures. In the process of learning and imitating foreign countries, Japan had a key factor. Before overthrowing the old government, it had sent a large number of people to European and American countries to study, or at least gradually learned the language, and they did a more important thing, which is to organize translation. In other words, they had translated a large number of Western conceptual systems before the revolution. So, why do we feel so strange when we look at their original documents now? They are completely separated from modern people? This is because Japan has long used the same Western concept to express its understanding of modern finance.

Of course, this is only the situation in Japan. I don't think there is any problem with Teacher Ho's judgment of Britain. He just said that Japan has a unique advantage of being a latecomer, and its own situation is quite special. Because Japan can give up this cultural path at any time and achieve huge changes, whether it is its own political philosophy or greater cultural subjectivity, which is unmatched by other countries.

In addition, I have some small questions I would like to ask teachers and teachers. First, how do we define the relationship between "finance" and "finance"? In the analysis of this book, does finance refer to part of finance? Because finance and finance are now separated, but it seems that in the description of this book, I feel that the two are mixed together without distinguishing them. Finance is related to monetary policy, interest rate policy, including national debt, etc. Of course, national debt can also be part of finance. What I want to ask is, whether it was Britain in the 17th century, Japan in the 19th century or the Qing Dynasty, were finance and finance themselves inseparable at that time? I think Japan has at least a tendency to separate at this stage because it has a central bank.

The second is the question of Charles Tilly's theory. Teacher Kazu pointed out in particular that Japan built a modern fiscal state without launching a large-scale foreign war, which challenged Charles Tilly's theoretical teachings, especially his classic book "Coercion, Capital and European Countries". View. I am thinking, do we only regard the real war as war, or do we regard preparing for war as part of war? Although Japan did not break out from 1880 to 1894, it had been preparing for war for a long time, and this book also confirms this point. Because Japan's goals were very clear, the military determined that the Qing Dynasty was the first imaginary enemy, and nationalism was prevalent in Japan for a long time, the national parliament actually supported the war against the Qing Dynasty. Therefore, I think the current introduction and demonstration of Japanese cases in this book do not seem to be enough to completely deny Tilly's theory of war.

Finally, when talking about the British model, it is the relationship between parliament and finance. In the United Kingdom, only a powerful parliament with fiscal power can develop and consolidate a modern fiscal country normally and smoothly. Teacher He also questioned the above view based on the case of Japan, because Japan gradually established a modern fiscal state without a parliament. Therefore, with regard to these two different models, I would like to hear further from the teacher.

Han Ce (Associate Professor of History, Peking University):

Following the thoughts of the two teachers, I will first talk about Japan. Teacher Cui just talked about Japan as a latecomer. In fact, the Qing Dynasty was also an object that Japan learned from. As soon as the results of the Opium War came out, Japan quickly learned the lessons of the Qing Dynasty's defeat, including the subsequent establishment of the Beiyang Navy, from which Japan learned experience and improved its naval combat capabilities.

In addition, in fiscal and other aspects, Japan did have a higher understanding of the West than in its contemporary Qing Dynasty. Teacher Cui just talked about Weng Tonghe in particular. He was indeed an example of not understanding Western financial knowledge and concepts. Although there were some people in the Qing Dynasty who understood better than Weng Tonghe, on the whole, from the emperor, the empress dowager, and the princes to Li Hongzhang, Sheng Xuanhuai, and then to the middle-level Ministry of Revenue personnel, they fell behind Japan as a whole. Moreover, in terms of the age structure of central financial officials, there is also a large gap between the late Qing Dynasty and Japan. Japan is a group of young, promising and motivated reformers in their 30s, while the Qing Dynasty is a group of older and accomplished officials. Therefore, there is a big difference in the motivation of these two groups of people.

Weng tonghe

The Sino-Japanese War was indeed a turning point for China and for the East Asian world. Before the Sino-Japanese War of 1894 - 1894, my feeling from reading the data was that the top management of the Qing Dynasty was mainly guarding against Russia. On the one hand, it was because Russia invaded the Pamirs Plateau area again in 1892; on the other hand, it was because Russia was building the Siberian Railway. Although it had not yet been completed, Xu Jingcheng, as the envoy to Russia, constantly emphasized the threat to Northeast China after the completion of the railway. Therefore, after the establishment of the navy in 1888, the Qing Dynasty devoted a lot of energy to land defense, mainly against Russia, because it did not feel that Japan was its biggest opponent.

I very much agree with what I told my teacher that we cannot simply push forward the outcome after the Sino-Japanese War (the Sino-Japanese Fiasco) and criticize the Qing Dynasty for how wrong this was and how wrong that was. In the 1895 - 1895 year, the Qing Dynasty made no preparations for war at all. The main task was to celebrate the 60th birthday of the Empress Dowager Cixi, while Japan was carefully preparing for war. In addition, many people in the top echelons of the Qing Dynasty did not know much about the situation at home and abroad. At that time, Japan had planned for a long time to drag the Qing Dynasty into the whirlpool of war, so the Qing Dynasty was forced to get involved without any preparation. Therefore, the outcome of the Sino-Japanese War did have a certain "contingency".

When I reflected on the three countries with my teacher, there were some basic conditions for comparison. For example, why could Britain and Japan develop into the current fiscal countries, but not in the late Qing Dynasty? One problem here is that after the suppression of the Taiping Rebellion in the late Qing Dynasty, a new fiscal structure was formed between the central and local governments. Did the late Qing Dynasty lack enough motivation to promote fiscal concentration? Because the next step in concentrating finance can be to use so-called long-term credit to finance. Or did the late Qing Dynasty have the motivation to achieve fiscal concentration, but in fact it was unable to achieve it? These two issues are closely related.

I think the late Qing Dynasty should have the motivation to centralize finance, because from the perspective of emperors and ministers, both wanted to centralize and control finance, at least in terms of benefits, there was a strong motivation. For example, Robert Hart told Prince Gong and others all day long about the benefits of concentrating finance. Moreover, from a realistic perspective, the Qing government's gains from tariffs did allow the high-level officials to see tangible benefits. Although there is motivation at the central level to promote this matter, various historical situations make it difficult to achieve. Why is it difficult to do? This is a relatively complicated matter, which involves the relationship between central finance and local finance. This is one of the very core issues in modern history and has been debated in academic circles before. One view believes that in the end,"local finance" was the result of the late Qing Dynasty, and the central government completely lost control; while another view believes that the central government still had strong fiscal control. In fact, many materials can be found as supporting evidence for both views.

I specifically reflected on these two opposing views in the book "The Change of Governor Jiang and the Politics of the Late Qing Dynasty". If the two views are contradictory and conflict, and each has reasons and examples, then should we consider using a new understanding to advance existing research? Teacher He pointed out in his book that the central government has not completely lost control over local finance, but I think the central finance is very weak compared to local finance. On the one hand, we see that although fiscal revenue rose to 80 million taels by 1890, the central government actually had direct control of only 20 million to 30 million taels, and many of them were fixed payments, so the central government or the Ministry of Revenue can directly manipulate money is very limited. On the other hand, local money is not only reflected in the accounts, but also a lot of hidden money, and the hidden amount is very large. According to relevant financial research, the amount concealed is even the same as the amount on the book. In the late Qing Dynasty, all places were crying poor, and no one dared to say they were rich, because if they said they were rich, they would be forced to give out money. But as Teacher He said, in the face of urgent matters, local governments can gather together. This shows that the local governments actually have money. However, when the matter is not urgent enough, the central government's reasons for asking the local governments to pool together are not sufficient, and the local governments lack motivation to pool together. Therefore, when faced with non-urgent matters, local governments can delay as much as possible. From this perspective, it is indeed difficult for the central government to control local finances.

Another point is that different types of governors are also very different. For example, Zhang Zhidong, governor of Shanxi, and Bian Baoquan, governor of Shaanxi, mentioned in Teacher He's book. They were both Beijing officials and were both northerners. When they first arrived as local officials, Shanxi and Shaanxi had relatively few likins, but the southern provinces were different. In addition, important governors such as Li Hongzhang, Zuo Zongtang, and Liu Kun, who were born in military service, were in charge of many armies and Western-affairs enterprises. Moreover, they had long-term positions in one place, so they had greater power. Although theoretically speaking, the Qing Dynasty could remove them at any time, it would not do so in practice. Moreover, these people would resign if they were unhappy, and the central government generally tried its best to retain them. Therefore, judging from all indications, although the Qing Dynasty retained the power to appoint or dismiss local governors, this power was incomparable to that of the Qianlong, Jiaqing and even Xianfeng periods. In short, the power of the central government has been greatly restricted, and politically it reflects a situation of "common governance". In addition, the financial relationship between the central and local governments sometimes involves mixed factors between China and foreign countries, such as Hurd's case. Generally speaking, I think that the late Qing Dynasty should have the motivation to concentrate finance, but it was difficult to do so because the fiscal relationship between the central and local governments had changed. Therefore, when the central government collects money from local governments, local governments will bargain in various ways. Like in the past, when it was central finance, local governments did not have so much room for bargaining. This was the social and economic structure of the late Qing Dynasty and the hidden situation that existed after the suppression of the Taiping Rebellion.

The book with the teacher also makes a comprehensive comparative analysis from aspects such as social and economic structure, human initiative, and contingency of events, so that scholars in history and social sciences can accept and recognize it. I particularly agree with and admire this research idea.

First of all, when talking about human initiative, I have just made some comparisons between the Japanese leaders in the late Qing Dynasty and the Meiji Period. I think we cannot criticize our predecessors because the situations they faced were too complex and diverse, and the opponents were too well prepared., which makes it even more obvious that our predecessors did not deal with them enough. However, the leadership of the late Qing Dynasty did have major problems. Before the Sino-Japanese War, the situation was that the authorities felt that the domestic order had been greatly improved and established the Beiyang Navy. They believed that they had reached a draw with the powerful France in the Sino-French War. All of this caused the high-level officials of the late Qing Dynasty to misjudge the situation, overestimate the military, economic and diplomatic development during the Westernization period, and underestimate the aggressive intentions of other overseas countries against the Qing Dynasty.

The current historical narrative is pushed forward based on the outcome of the Sino-Japanese War, believing that the consequences of the fiasco of the Sino-Japanese War should be borne by the people who came to power ten years ago, and all the blame will be hit on them. They should be responsible, but it is not necessary to shift all the responsibility to them. This is a problem. Of course, the leaders of the late Qing Dynasty did have limitations. For example, after the Sino-French War, one of the top leaders, Empress Dowager Cixi, had a great wish to resume making money. At that time, many professionals believed that it would be difficult to recover, and the normal situation should be to further unify the currency. Why should we resume making money? We speculated that her psychology was that she wanted to regain a city for her husband, Emperor Xianfeng. Because after the Taiping Rebellion, the Qing Dynasty's finances were in chaos, and Xianfeng issued paper money wantonly, making a mess. Therefore, it was equivalent to Cixi restoring order and wanting to restore a city for Xianfeng. However, this policy was ultimately not implemented.

For another example, at that time, in the late Qing Dynasty, they wanted to establish a bank, but the Ministry of Revenue opposed it because the banks were all contacted by Li Hongzhang. The Ministry of Revenue believed that Li Hongzhang had already occupied a large amount of property, and now that he created a bank again, his power would be greater. Hurd was in a similar situation. Whenever he showed signs, Li Hongzhang and local governors (such as Zhang Zhidong) immediately opposed him, saying that Hurd had so much property and could not be allowed to hold more power. Therefore, Hurd was restricted layer by layer, making it difficult to carry out many things. In Teacher He's words, at that time, the Qing Dynasty began to make some long-term credits despite the central government's limited financial resources, such as issuing foreign debts and national bonds, and borrowing loans from abroad. However, Weng Tonghe, Minister of the Ministry of Revenue, and many senior officials opposed borrowing foreign debts, so things were difficult to implement. In short, this was all a matter of people's initiative at that time.

Secondly, in an accidental event like the Sino-Japanese War, after telling the teacher about a "credit crisis", one would find that a series of measures taken by the Qing Dynasty showed that it could develop into a modern fiscal country. I think this is an opportunity, a contingency of events. Sometimes doing things requires some opportunities, but this opportunity seems to be more than just financial.

We saw that after the Sino-Japanese War, Li Hongzhang of the Huai Dynasty fell, and Liu Kunyi and others of the Hunan Dynasty also lost their right to speak due to the unfavorable war. Therefore, the war temporarily scattered local power. At this time, everyone wanted to go to the national disaster together, and foreign debts were bound to be borrowed. Therefore, the central government of the late Qing Dynasty borrowed foreign debts to repay the compensation through mortgage, that is, tariff mortgage and lijin mortgage. The three loans during the 1894 - 1894 mortgaged many things. By the time of Gengzi, all the salt tax and likin the southeast region were mortgaged. At that time, the governor did not dare to violate foreign debts, so under such circumstances, the governor certainly could not delay, because these were the most urgent matters and must be repaid on schedule.

In this sense, Lijin and local finance and taxation are used as collateral to repay debts, but in fact, they are recovered from the local governments to the central government in disguise. Although the money has not reached the central government's accounts, it is still being repaid to the central government. Then the customs collects these financial resources, which theoretically means that these financial resources will be the central government's money after paying off the debts. By the New Deal in the late Qing Dynasty, the central government gradually recovered local finances. After the Gengzi Incident, the country's income only increased to 100 million yuan, which increased to 300 million yuan at the end of Xuantong. In the past ten years, it increased by so much. Although there were factors such as economic development and increased tax revenue, it was mainly due to the concentration of local money. Therefore, there may be more complex factors in the development of the path from the 1894 to a modern fiscal country after the 1894 - 1894 era.

Zhang Changdong (Professor, School of Government, Peking University):

I learned a lot from listening to the speeches of several teachers just now. Some points are somewhat similar to what I was thinking before, and they also deepened my understanding. I will mainly talk about my thoughts and thoughts on three points.

The first point, which was mentioned by the previous three teachers, is theoretically the discussion between war and national construction. In the past, most people would think that civil wars are more destructive and more destructive to national construction. However, some studies over the years have also pointed out that under certain conditions, civil wars have a constructive effect on national establishment.

In addition, like the outcome of external wars, Teacher Han just made it very clear that there are many accidental factors behind it. before International OrganizationThere is an article in the previous article that discusses the relationship between war and state construction, and believes that there are many contingency conditions, so the relationship between the two should be a relatively complex chain of cause and effect. Especially during the preparations for war, countries need to tax or borrow, and the details here deserve in-depth exploration.

I wrote here in my notes called "Betting on the National Fate". Teacher Han also talked about the issue of the National Fate just now. Japan, which has been preparing for so many years, is actually gambling-winning the war will lead to a turnaround, and losing will be another outcome. For example, Britain and Japan won the war and achieved trade expansion. Of course, Japan will also receive large amounts of reparations. Japan borrowed money from Britain in preparation for war, which was somewhat of a gamble for those in power. Under the circumstances at that time, for Japan, borrowing money first to survive was the most realistic strategy. But when Japan won, it quickly achieved trade expansion and tax revenue increased rapidly. Correspondingly, the pressure on repaying loans eased. More importantly, the confidence of ordinary people in Japan in borrowing will also double. The victory of the war will directly boost the confidence and future expectations of the people in Japan, which will in turn reduce the tax collection costs of the Japanese government. In short, war and its victory achieve a virtuous cycle.

However, assuming that the result is defeat, this virtuous cycle no longer exists and will become a vicious cycle instead. Under such circumstances, domestic and foreign trade unions began to shrink, as in the Qing Dynasty, and they would face huge reparations and be forced to borrow from foreign powers. To a large extent, external borrowing has squeezed the development of the domestic bond market. From this perspective, I feel that the content in my teacher's book more supplements this logical chain rather than challenges the theory of the relationship between war and the state.

Moreover, judging from the comparability of the wars between these three countries, the Qing Dynasty was indeed more embarrassed, because the domestic war, especially the Taiping Rebellion Movement, was too destructive to the domestic economy, seriously damaging the domestic political order and economic market, and had a very negative impact on the construction of the country.

The second point is of particular interest to me, because I plan to write about China's fiscal and tax reform after 1949 and the political and economic logic behind it, but until now I have not dared to study China's fiscal and tax history for such a short period of time, so from this point, I particularly admire and my teachers for having such strong courage and confidence to devote themselves to the study of the fiscal history of three countries. Teacher He's book mentioned that behind the fiscal and tax reform is actually some political struggles and a political game between different factions. Like the very vivid examples mentioned by Teacher Han Ce just now, such as the doubts and obstacles Li Hongzhang encountered when he wanted to establish a bank, they were actually the constraints of power factions encountered during the reform process. Of course, Japan faced the same problem during its reform. On this issue, some documents on reform in the 1980s and 1990s were actually very enlightening.

I am thinking whether in these three countries, reformists like Japan and the United Kingdom successfully grasped power through a series of accidental and structural factors, and then truly implemented the reform measures. Like the Qing Dynasty, either everyone lacked the awareness of reform, or the people with a sense of reform lacked the ability to achieve power integration, so the reform died in the early stages. These thinking logics are inspired by the content of this book. I feel that they are not enjoyable enough to read, including the "Process of Actors" mentioned in the book. Of course, this part may be limited by space. If each country were written in a separate book, there might be more scenes to write about actors.

The third point is the application of institutionalism and institutional change theory. I think the issue of path dependence is also involved here, including the issue of "sequence" emphasized by teachers. One of the most controversial points in methodology is how to select and how to select a so-called "critical moment"? Comparing Britain, Japan and the Qing Dynasty together, I think the situation in the Qing Dynasty was slightly more special. The book tells that these countries all have a process of "state building", followed by measures such as fiscal reform. However, in terms of comparability between the times, the late Qing Dynasty was actually a process of "state rebuilding." That is to say, from the Kangxi to Yongzheng period, the Qing Dynasty was the founding stage of state construction. For example, Yongzheng discovered that there were many financial crises in politics, so he carried out a series of political and fiscal reforms (such as "returning to the public after losing fire"); while the Qing Dynasty during the period discussed in this book was actually in a very serious stage of political decline, and the entire country faced a situation of internal and external troubles. Compared with the central government, the domestic local ruling power was relatively strong. Therefore, on a larger level, the political structure of the late Qing Dynasty may be quite different from that of Britain and Japan. For example, although Japan and the United Kingdom have conservatives and reformists in the country, their overall line and direction are the same, and everyone is working hard in the same direction as a whole. If we apply Mancur Olson's theory of "profit-distributing groups", we will find that there were many profit-distributing groups in the late Qing Dynasty, and it was difficult for the state to integrate and control local forces. In short, the challenges faced by the late Qing Dynasty were far from the same magnitude as those faced by Britain and Japan.

The above are my three thoughts after reading, as well as some inspirations for me. Thank you, teachers and all teachers.

Tian Geng (Associate Professor appointed by Dean of the Department of Sociology, Peking University):

The teachers just now mainly talked about a certain part of the book. As a sociologist, I would like to consult and teach on two aspects. One is theoretical design, and the other is relatively conscious issues.

I understand the structure of Teacher He's book to include three levels. The first level is the reconstruction of the politics, economy, and history of the three countries. In fact, it is an explanation around the success or failure of the modern national fiscal system in three dimensions. This is the historical body of a modern fiscal country. The second level is the "credit crisis" that has emerged in the field of historical institutions and its resolution strategies. This is the core of the analysis of the so-called "modern fiscal state" in this book. The third level is the key issues in comparative historical methods in social sciences, such as the choice of key time points, multiple possible consequences and their elimination, the determination of time sequences, and the review of choices based on historical situations rather than extrapolating from results. These are all methodological issues of comparative awareness.

The first level, which the teachers have talked extensively just now, I will mainly talk about the latter two levels. The first is the second level, that is, theoretical issues. Among the three comparative cases, the historical period chosen in the English part of this book is the longest, from the 17th century to before the Seven Years War, while the Japanese part has the shortest time, and the Chinese part, plus the last chapter, has some extension, but in fact China itself has a relatively short period. Then, the case of China and Japan is more similar to a review of the "reform history" of the fiscal state. During the time covered by this book, England's "fiscal state construction" is far more than just a reform history. It not only experienced rapid changes in party struggles, political regimes, and national defense systems caused by civil war, but also faced intensive dynastic wars after entering the 18th century. For example, starting in 1700, the succession war with the Spanish royal family and the global hegemony with the French Bourbon Dynasty. The Seven Years War touched very deeply on the changes in the credit system, namely, why Britain was forced to turn to the continental mercantilist system that the Whig System was striving to avoid to resolve the common crisis brought about by the war. The treatment with the teacher indirectly puts England's history and time choices in the process of confrontation with mercantilism. It first seeks England's uniqueness, and then examines the process of confrontation between England and the European continent. The choice of this period fully reflects the history of regional competition in Europe. How to balance this feature in the cases of Japan and China is actually a very important issue. The history of reform certainly includes transnational factors, but under a relatively short period, how to coordinate the establishment of a fiscal state as a history of reform and the construction of a fiscal state as a regional political economy? Teacher Han has just talked about the historical facts of regional competition in China's case, especially the transformation of competitors from Russia to Japan, which brought about the impact of the late Qing Dynasty system reform.

Correspondingly, the concept extracted from institutional analysis in this book, the crisis of creditism, roughly includes "long-term crisis" and "short-term crisis." The "long-term crisis" refers to the transformation of a modern fiscal country that the teacher discussed in the book, leaving the territorial country, centralizing fiscal management, and then realizing the transformation of a modern fiscal country. During this process, reform options will be tried and successful or failed. In addition, there is a very significant "short-term crisis", which in sociological terms is a reform situation full of urgency. As several teachers mentioned just now, identifying and clarifying issues that need reform is one aspect, and carrying out actions in the context of complex and diverse power checks and balances systems, party and government systems, and reform ideologies is another aspect. Teacher Du mentioned a core point earlier, that is, the "patrimonial pattern" actually exists in all cases, but its degree of influence on different countries and their institutional reforms varies. Similarly, Teacher He's book shows the process of different countries responding to the credit crisis and the differentiated reform characteristics it reflects. And this characteristic can determine the extent to which problem-solving methods are put into practice.

There are two books related to Qing history that can reflect the country's reform situation and reform background in the face of crisis. One is Mr. Shi Quan's "Political Situation in the Late Qing Dynasty Before and After the Sino-Japanese War", and the other is similar to Polacek (James M. Polachek's "Qing Dynasty Internal Struggle and the Opium War". Both books deal with institutional changes and current responses to crises.

The credit crisis and its overcoming by countries are common problems faced by almost all pre-modern countries during their transformation. The key starting point of this book is that behind the differences we cannot list, many countries are facing a common sense of crisis, and teachers. The refinement and interpretation of the common sense of crisis in the book can be regarded as a model for historical sociology. However, this long-term and widespread crisis and perception of it are not only a criterion for testing different reform measures (which reform measures can be advanced and which cannot), but also profoundly affect the understanding and judgment of those in power on the situation and situation. This is also the common highlight of the two books ("Political Situation in the Late Qing Dynasty Before and After the Sino-Japanese War" and "Civil Struggle in the Qing Dynasty and the Opium War"), which richly demonstrate the role and consequences of long-term crises in the form of short-term reform.

"Political Situation in the Late Qing Dynasty Before and After the Sino-Japanese War"

"Qing Dynasty Internal Struggle and the Opium War"

When reading the History of England in this book, I will also think of the issues Adam Smith talked about in Volume 4 of The Wealth of Nations. This question specifically means that in the mid-18th century, Britain had two different views on resolving the war crisis, one was the Whig view and the other was the Tory approach. The Tories advocated a land wealth system, emphasizing the direct management and possession of colonies, and sharing the financial crisis for the mother country. This is what the Whigs disagreed with, because behind it were successful North American colonists and British manufacturers who needed to ensure a large producer and market and could not accept strong centralized land management solutions. This is also the key point mentioned at the end of the teacher's book. England's long-term Whig politics has had important partisan disputes, which strongly restricted England's transition from a commercial republic to a wealth-seeking monarchy.

Nanir (L. B. Namier and his "History of Namir" believe that "politics" is a key perspective for understanding British political development and line reform. In other words, some powerful ministers around the king and their cliques are considered to be the core of British political operations. In contrast, some historians believe that the party struggle between Whigism and Tory is not a struggle for political power itself, but a difference in line involving the concept of governing the country. In fact, Mr. Shi Quan's book also touched on the issue of whether the factional struggle in the late Qing Dynasty was a political struggle or a debate on its substantive content. The subtlety of his book is that it attempts to solve institutional difficulties in the process of political history. These are some of my feelings about the "substantive theory" in the middle.

Finally, let's talk about comparison methods. A particularly valuable part of the book with Teacher is that it challenges some of the basic methods that constitute comparison. One of this basic means is manifested in what Teacher Zhang just mentioned, what is a "critical moment" and how to choose a "critical moment"? Should the choice of critical points and turning moments be judged through fiscal historical data or through the sense of political rhythm behind the data and historical archives? The second is the comparison between commonality and opposite sex. The content mentioned by the above teachers is a very critical issue for comparative historical research. The core point is that for building a modern fiscal country, the differences between early exploration countries and late-development countries in handling the same reform issues. In other words, when comparing the UK with Japan and China, what needs to be considered is the differences between early developing countries and late-developing countries. For the latter, the position of late-developing countries determines to some extent that they have a "learning and acceptance history" process, and this process has an impact on the reform effect. In terms of historical research on institutional change and construction, country or regional case comparisons are themselves intertwined with institutional evolution. Historical systems may not be just a "hard assessment" that can be differentiated by traditional regions (if you can pass, you can build a system, but if you can't pass the system, you cannot build it). I think this can just prompt comparative historical research, because studying each case in pure isolation has great challenges and risks. On the other hand, learning from the history of advanced countries by late-developing countries is itself part of their reform, but it needs to be considered and handled more carefully in terms of methods. In short, the book He Teacher provides a very valuable attempt and exploration in the field of comparative historical research.